(more to come)

Dr. ROBERT M. CUNNINGHAM

CLOUD PHYSICIST / METEOROLOGIST / ATMOSPHERIC SCIENTIST

FOG RESEARCH on MOUNT WASHINGTON

In 1938 -1942, my undergraduate years at MIT, I took on as a side-line the chemical analysis of two years of fog water collection on Kent Island. A paper on this subject was published in the Bulletin of the AMS dated April 1941. Cunningham R.M., "The Chloride Content of Fog Water in Relation to Air Trajectory."

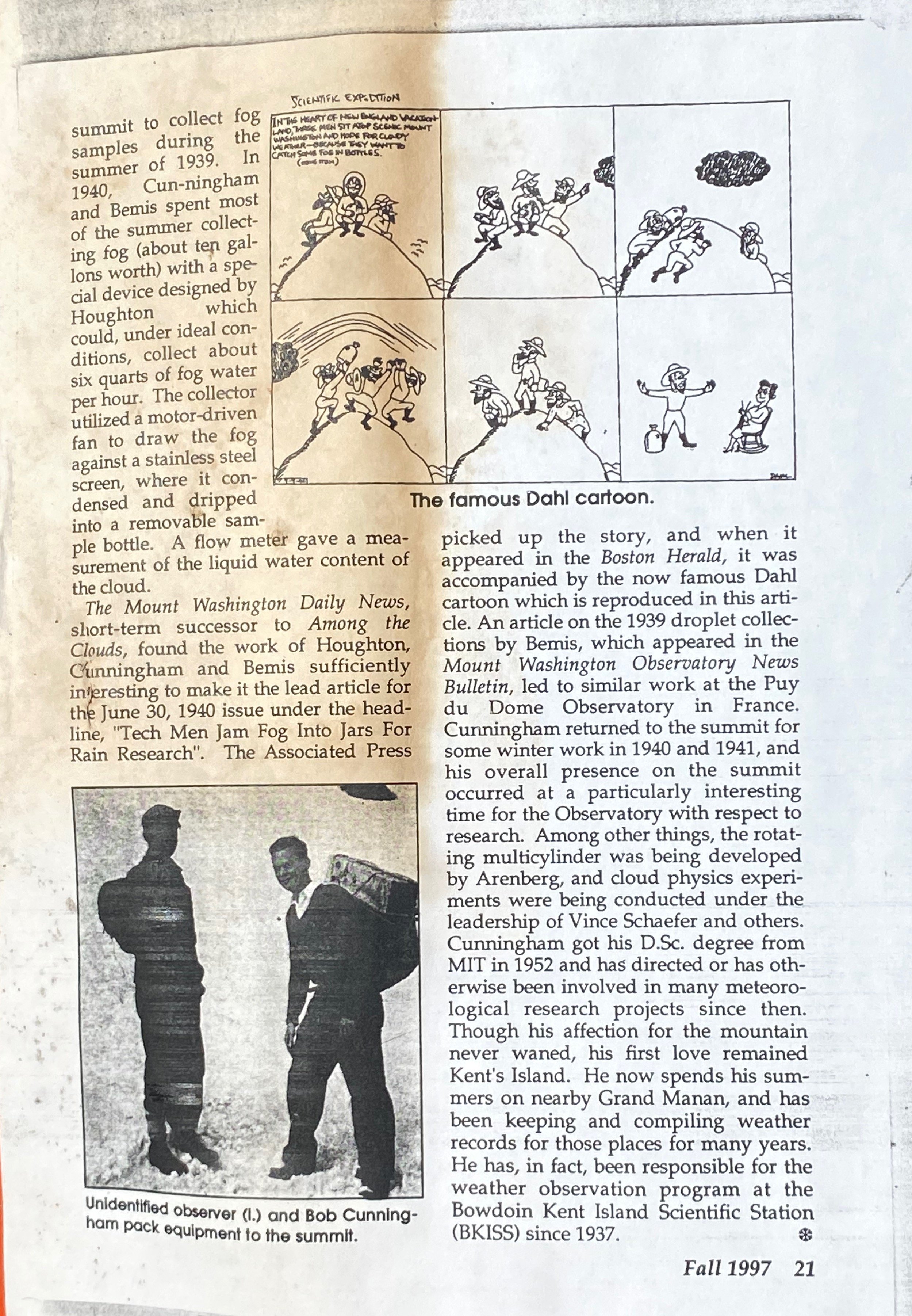

In the summer of 1940 I again worked for Professor Henry Houghton,(archives here) this time on Mt. Washington collecting fog (cloud) water samples with his large tunnel-type collector. In the picture below I’m holding a jar of fog water.

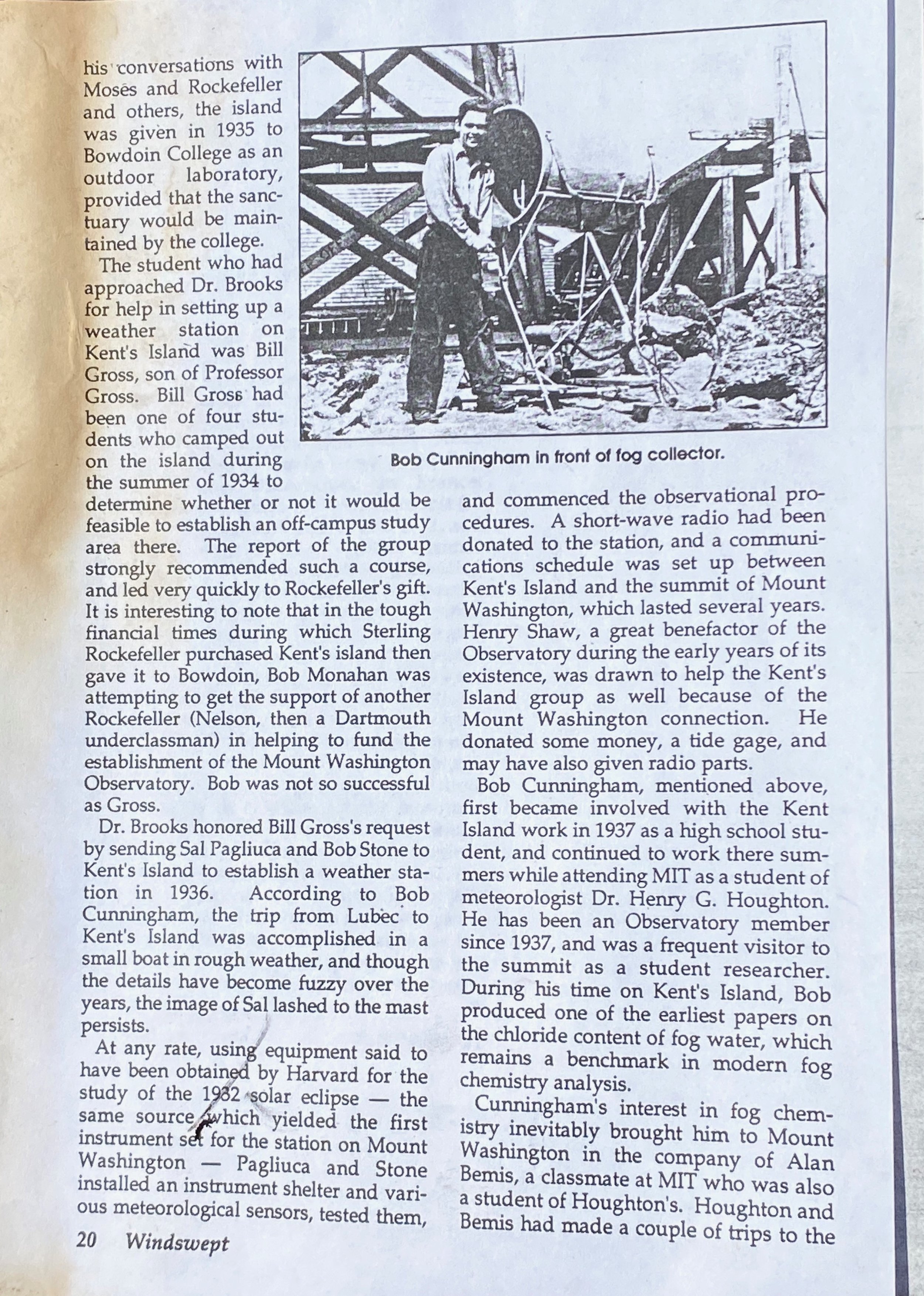

Perhaps my call to public fame came from this job. My activities were reported in the local tourist paper that was published on the mountaintop. Dahl, a famous Boston cartoonist, caught the spirit of the endeavor in a cartoon in the Boston Herald, the leading Boston paper at the time.

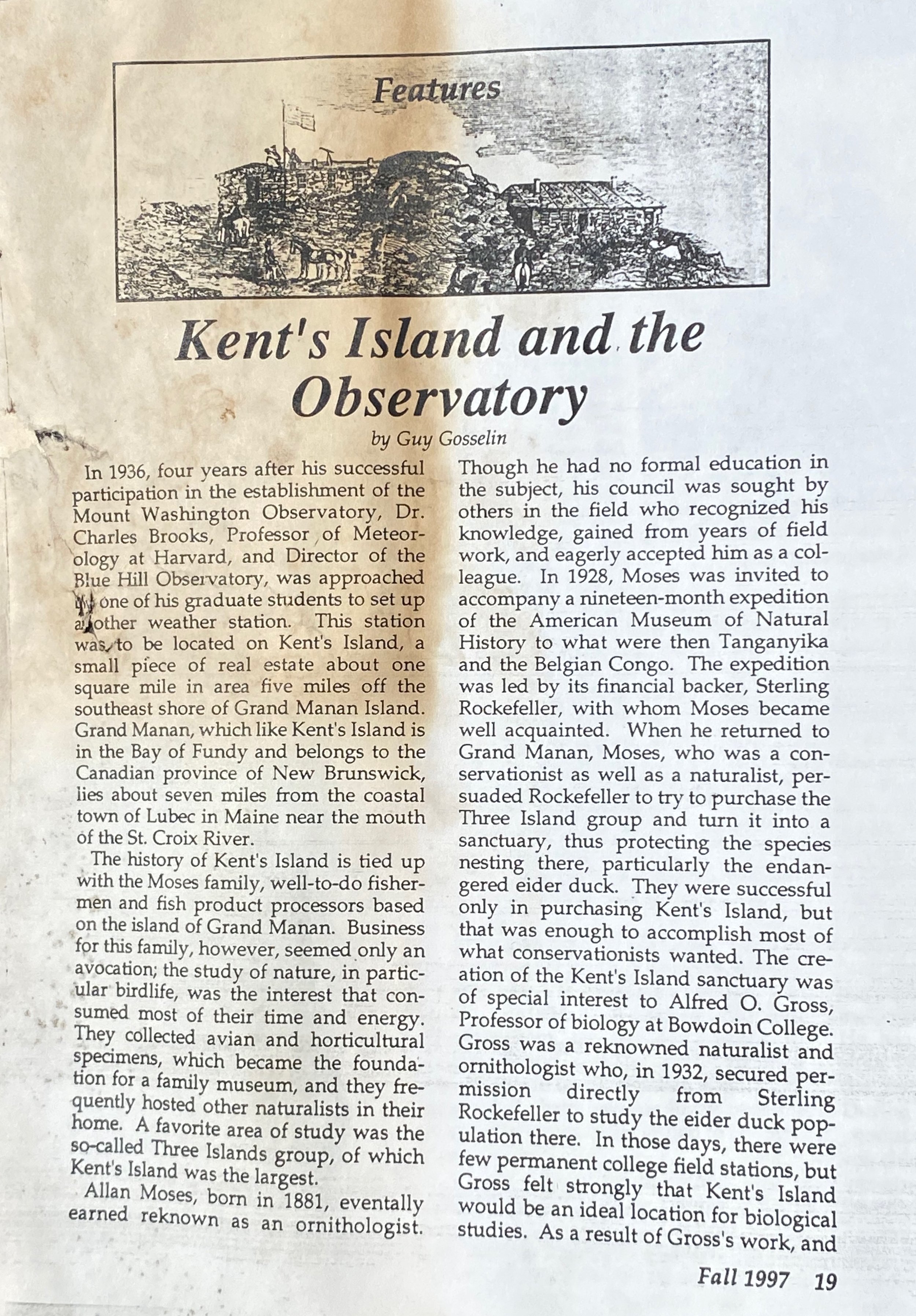

“Cunningham’s interest in fog chemistry inevitably brought him to Mount Washington in the company of Alan Bemis, a classmate at MIT who was also a student of Houghton’s. Houghton and Bemis had made a couple of trips to the summit to collect fog samples during the summer of 1939. Cunningham and Bemis spent most of the summer collecting fog (about ten gallons worth) with a special device designed by Houghton which could, under ideal conditions, collect about six quarts of fog water per hour. The collector utilized a motor driven fan to draw the fog against a stainless steel screen, where it condensed and dripped into a removable sample bottle. A flow meter gave a measurement of the liquid content of the cloud.” -Guy Gosselin

In 1997, WINDSWEPT, the journal of the Mount Washington Observatory published this article about how Bob’s early fog research connected their activities with those of The Bowdoin Scientific Station on Kent Island.

DE-ICING, BERNIE VONNEGUT and ALAN BEMIS

After graduating in 1942 from MIT I joined the aircraft-icing project in the meteorology department and expanded my interest and knowledge in cloud physics. The group at first was composed of Jim Dotson, Bernie Vonnegut, Robert Katz, and myself. We had an unfortunate casualty early on when the pilot and Jim Dotson, head of the group, were killed in a crash of a Lockheed Electra aircraft (the same model used by Amelia Erhardt). We were trying out the feasibility of using this aircraft for icing research. Bernie Vonnegut and myself had a check flight on this aircraft just the day before. Bernie is later known as being the first to use silver iodide to seed clouds. Bernie became the group leader and we continued to do icing research at MIT and aircraft icing research and testing. I spent several winters in Minneapolis flying on military aircraft, mostly a B-25, developmenting hot wing de-icing systems - hot air from the engine was piped to sensitive areas in the wings.

Bernie invented an instrument to measure icing rate. This instrument got me involved with an effort by the Air Force weather reconnaissance squadron in Manchester, NH. Spending part of a summer at Gander, Newfoundland, we instrumented a B-17 reconnaissance aircraft with our new instrument to measure the rate of icing. We flew at both 400’ and 10,000’ in this aircraft across to Iceland to support the huge fleet of aircraft returning from Europe at the end of WW II..

Bob C. in co-pilots seat of “our” B29 about 1952..

13. At the end of WW II the aircraft icing programs at MIT ended and the program was shifted to Cleveland under NACA (predecessor to NASA) where a huge refrigerated icing tunnel was built to simulate aircraft icing conditions. The Minneapolis group also expanded the icing research on Mt. Washington. The radar and weather radar development and detection also ended with the closing of the Radiation Lab at MIT. The MIT meteorology department could then explore the uses of weather radar. A new weather radar program was started at MIT after the Radlab closed down. It started to explore this new tool for observing weather in three dimensions, in particular, looking aloft. The department started the weather radar group and expanded rapidly; it shortly obtained an Air force B-17 for taking cloud physics measurements (for a short time after the war there were extra airplanes and pilots to give to crazy meteorologists).

Bob atop instrumented cloud physics B-17 ~1946

CUNNINGHAM’S CALLIOPY: B29 crew along with Fred Spatola showing our crew’s artistry; this lasted only one day after the base General had one look at it.

I was in charge of the cloud physics portion, Alan Bemis was the head of entire weather radar program. With both an airplane and powerful (at that time) ground radar, we explored jointly the ice crystal, snow, and rain areas of New England storms. Several papers were published including one by myself explaining, the so-called “BRIGHT-BAND” for the first time with in-situ observational backup and theoretical considerations of its existence.

USAF C-130

The instruments included most of the standard meteorological sensors of those days plus some unique ones, in particular a 3cm refractometer mounted to avoid hygrometeors (cloud, rain and ice (snow) particles). This highly sensitive device in a small fraction of a second could measure the vapor pressure changes later corrected for small changes in temperature and pressure. This was an ideal sensor for studying the structures of clouds many of whose boundaries were found to be very abrupt. Because we had this instrument and because of the way it was mounted on the C-130, we became involved in a number of projects concerned with high frequency radio propagation. We explored the possibilities of long distance propagation due to large changes of refractive index at the top of large areas of cloud sheets, and we explored the electronic “noise” created in systems which used two paths to measure distance. There was a problem when the two paths intersected different cloud configurations.

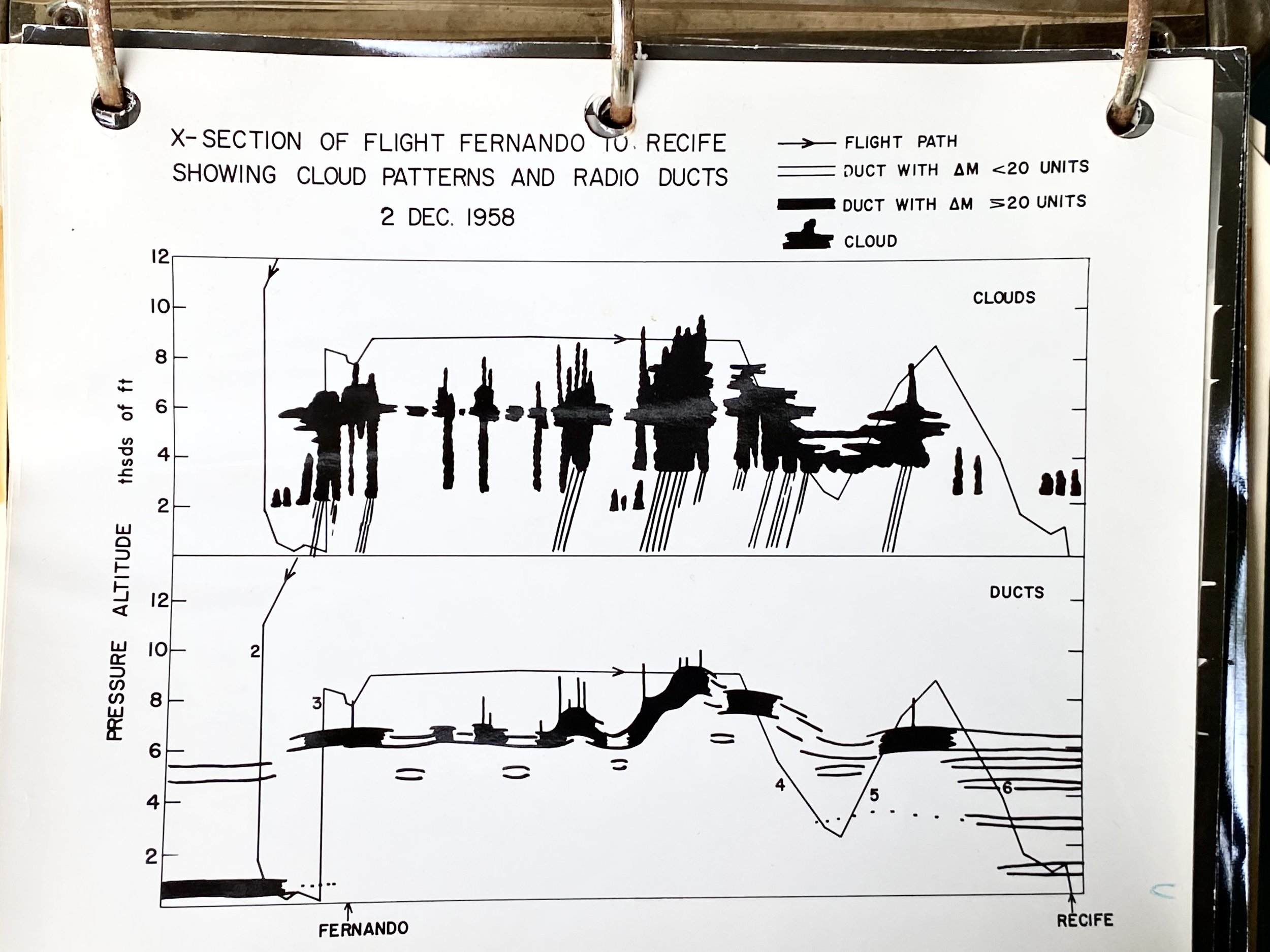

1958 An early project, just before the advent of the satellite era, took us to Recife, Brazil, and on across the tropical Atlantic to Ascension Island, (with a farm on top of a lone mountain, but the rest a bleak no mans land). The east again to a few miles west of the Congolese African coast, were we took a sounding from clear weather down through 10 thousand feet of solid cloud to 400 feet above the ocean. These flights were made to explore the possibility that the sharp refractive index changes across the cloud tops were consistent enough to permit microwave frequency radio transmissions across the tropical Atlantic from blimps at the top of the moist layer.

Other flights involved support for early flights of the Mercury project at Cape Canaveral where there were problems with the guidence systems due to abrupt changes in the refractive index patterns at the border between clouds and clear air. A short time after these measurements these same rockets carried men beyond the earthly atmosphere.

1958-61 Cape Canaveral for Mercury launches

Other flights at this time involved support for early flights of the Mercury project at Cape Canaveral where there were problems with the guidence systems due to abrupt changes in the refractive index patterns at the border between clouds and clear air. A short time after these measurements these same rockets carried men beyond the earthly atmosphere.

1961 PROJECT Hi-Q Mt.Humphreys FLAGSTAFF, ARIZONA

20. Several weather modification test programs were pursued. I ran a field effort of a joint Navy, Army, and Air Force project in New Mexico to study the effect of silver iodide seeding on cumulus clouds that formed over the Desert Mountains. “My” C-130 plus two small aircraft and ground cameras were used to follow precisely the cloud region seeded. The lack of this ability has been a major reason that cumulus-seeding projects had been unable to give definitive results, at least to the satisfaction of critical scientists. This project was not allowed to continue long enough to arrive at definitive results. During this period I conducted a critique of a Navy Vietnam seeding project, coming to the conclusion that it was ineffective for military purposes.

SEEDING CLOUDS OVER GERMANY

One of the interesting side trips (I think in the '60's) was to Germany with a German cloud physicist employed by the US Signal Corps (Dr. Aufenkampf) We were to demonstrate the clearing that might be possible in winter stratus or stratocumulus clouds north of the Alps, These types of clouds make this area of Germany particularly dark and cold during the winter. We seeded the undercast (clouds as seen from above) with dry ice pellets. We were calmly following the cleared hole, probably several miles wide, when the communication with the ground became very active, we were apparently getting close to the Russian controlled area, i.e. GET OUT! We had to circle and follow the hole from a distance as it disappeared from view into the East. One obvious problem with this scheme was that the winter winds above ground are usually very fast moving, so for people on the ground the seeding provides only a momentary glipse of the sun. From this side of the Atlantic it seems extraordinary that a government would fund such a project simply to bring a moment of relative happiness to their people!

1962 Clear Air Turbulence

1963-64

Edward Teller’s misunderstanding

I also recall a meeting in Washington on what the federal government should be doing in the weather modification field (also in the 60's?). This was an informal meeting of about 6 people including science administrators and scientists, principally from the defense science branches and the National Science Foundation. I was surprised when Dr Edward Teller walked into the room. He was invited just because he was interested in weather modification; perhaps he was looking for an area that could explode with world interest as had his previous project. I was, however, disappointed with what he said; he followed Langmuir's belief that simply burning a torch with a silver iodide solution in the fuel could change the whole world's weather. He had no appreciation of the vastly different scale over which weather systems occur.

1974 APPLIED RESEARCH CROWDS OUT BASIC SCIENTIFIC reSEARCH

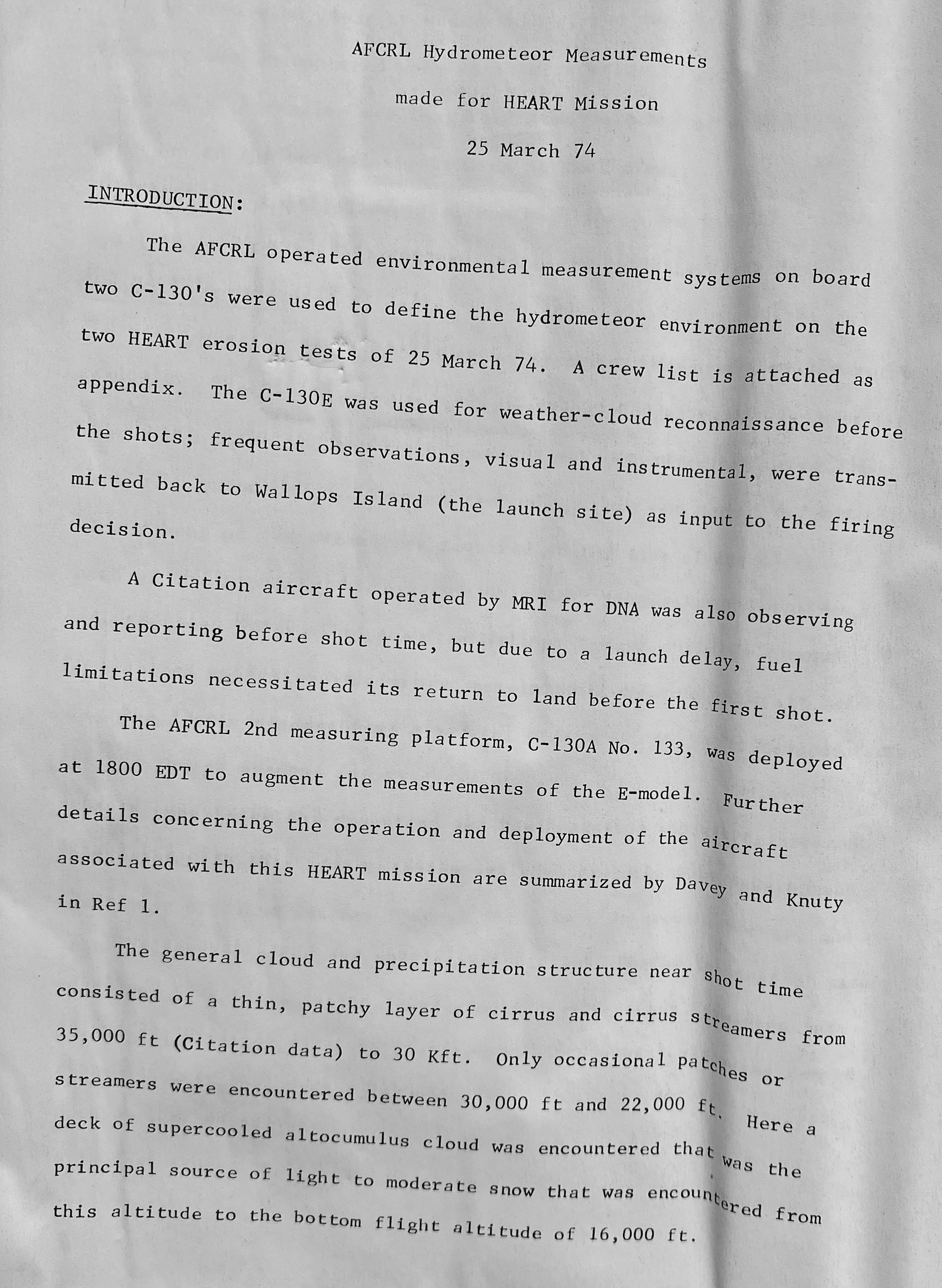

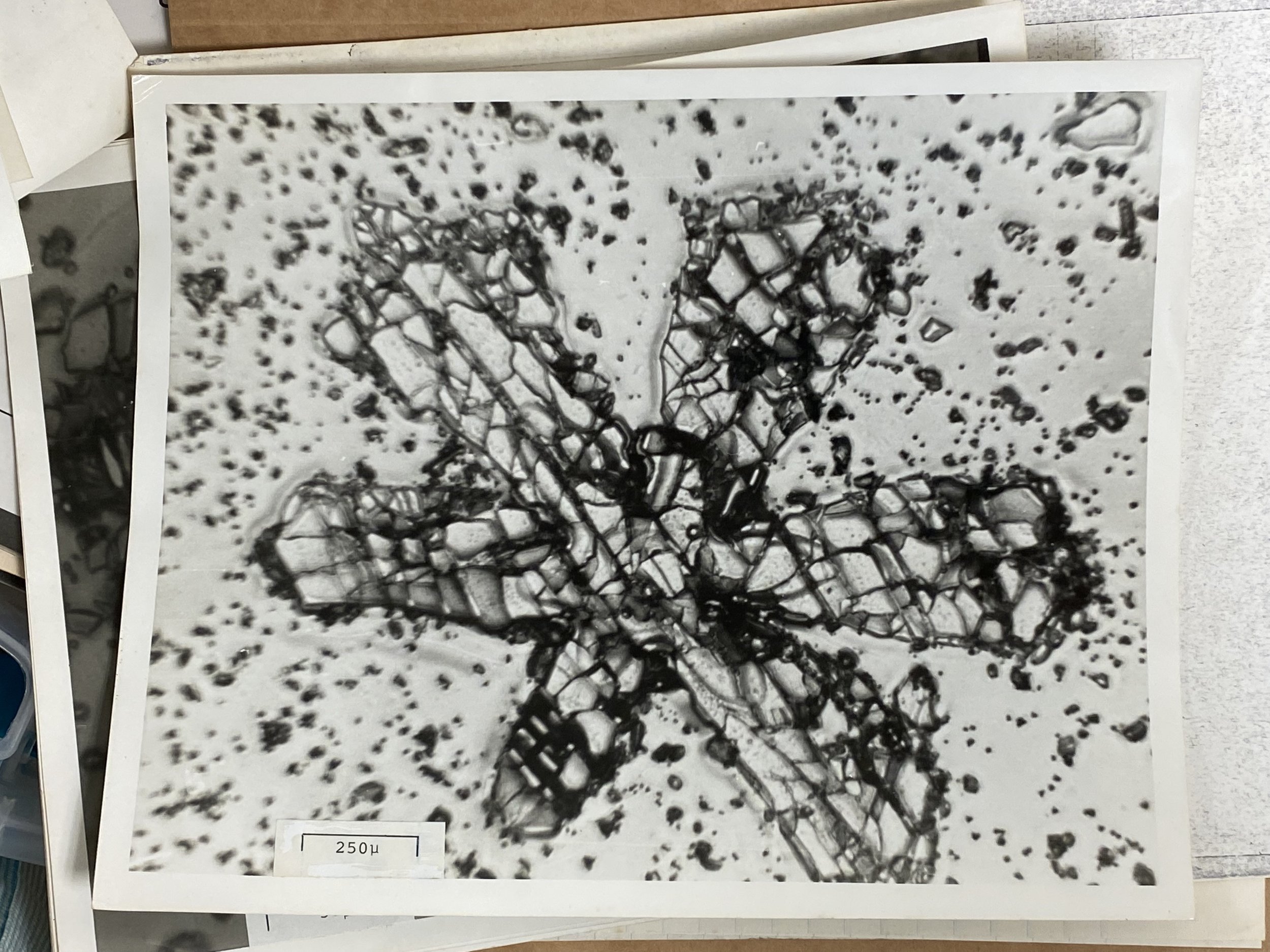

I worked on a snow/ice crystal erosion project jointly with the weather radar branch of AFCRL. This project was centered at the NASA Wallops Island test range, where they were interested in what happens to missiles when they re-enter the atmosphere (the demands of applied research for years had been crowding out the previous priority of basic scientific research). We flew in the altostratus/cirrostratus cloud altitudes measuring particle type and size distribution while large surface weather radar measured the particles' return signal. A short time later the test rocket passed through this region and was eroded by these particles while the weather radar continued to take measurements. The relations found during the aircraft passes (radar signal versus particle properties) were applied to the radar measurements at the time of the rocket track to obtain an estimate of the destructive properties of clouds on rockets.

24. Later in the ‘70’s we were heavily involved with a different test site that ended across the international dateline in the central Pacific’s large Kwajalein atoll. Here we made high altitude flights measuring refractive index and the cloud/ice crystal through which rockets made their descent. These flights gave small refractive index changes, but showed some turbulent regions and particles of important sizes.

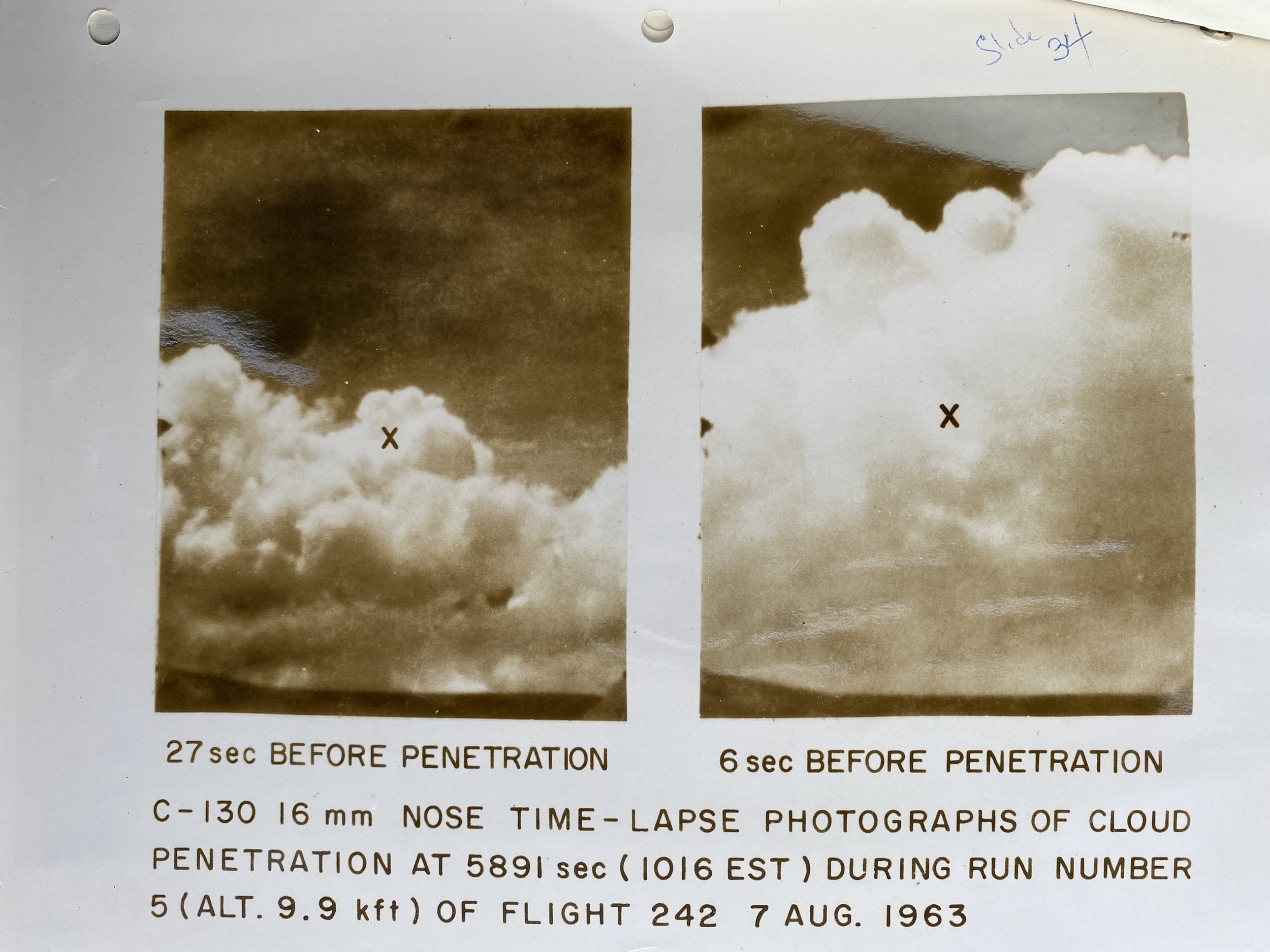

25. Except for the application type projects above, the purely cloud physics investigations centered on cumulus cloud dynamics and particle growth studies. Here also there were applied fields of weather modification and flight safety. There were several summers where the aircraft made measurements in the growing New Mexico mountain clouds while several large cameras pictured the region from nearby hilltops. A similar project was run along the east coast of Florida where the aircraft probed the line of sea breeze Cumulus-Congestus and Cumulo-Nimbus. The cameras kept track of the cloud growth from the offshore islands.

26. We carried out an amusing performance over Cocoa Beach in Florida. We formed an inline flight formation utilizing all the aircraft we had in our project. First in line were a U2, then two fighters (a T33 and an F100), then my C130, and then a small, private aircraft. We flew at low altitude (about 500 ft) on the approach to Patrick AFB, over the beach in front of the apartments where we were living, over my wife and the pilot’s wives playing bridge outside; they were startled to say the least. We were able to stay for a while in a close formation, a great salute!

Our C-130 #133 and Bob: ready to go flying in Oklahoma on project “Rough Rider”

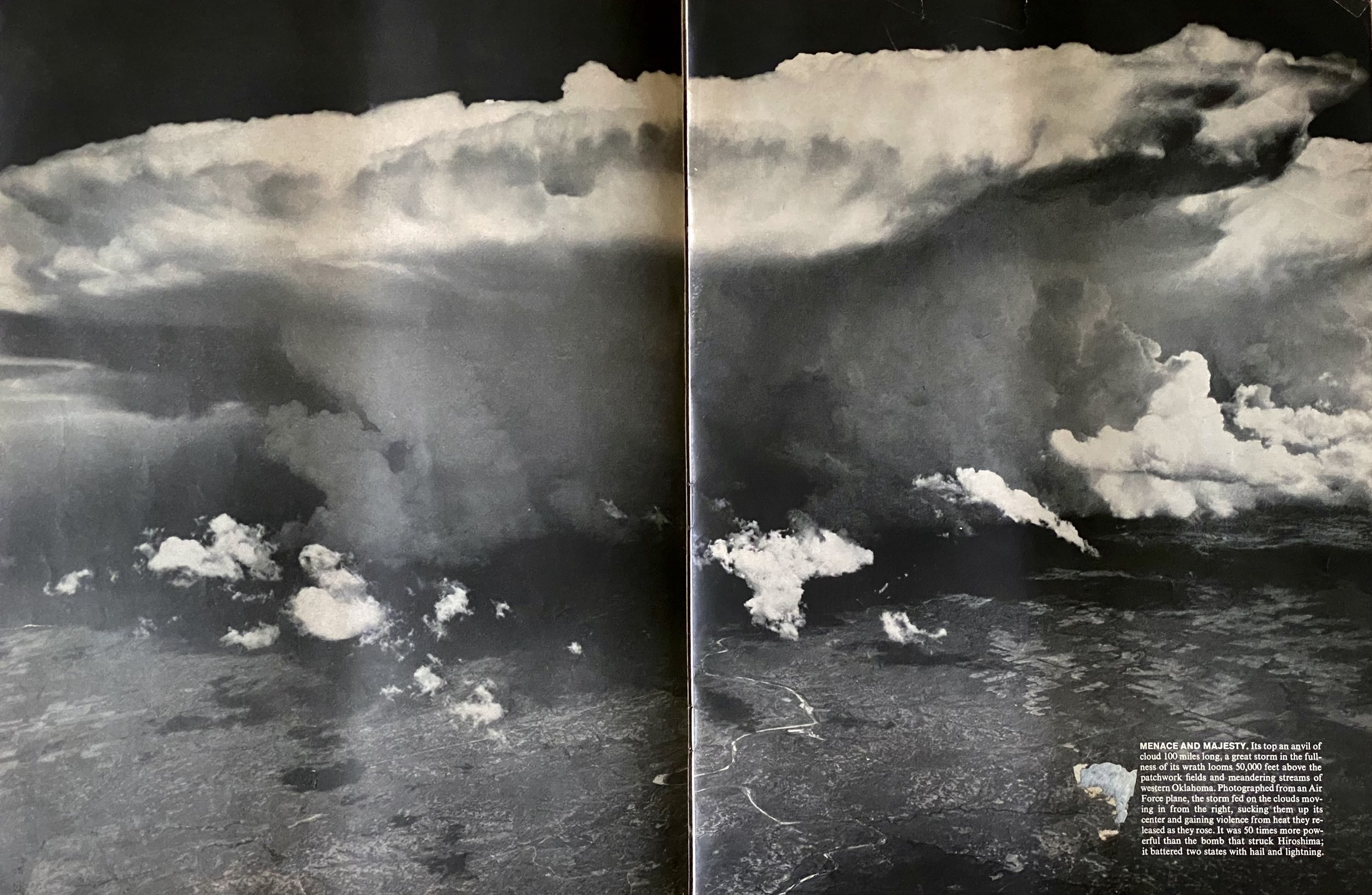

MENACE AND MAJESTY: Life Magazine CENTERFOLD 1963

Violent spring storms in Oklahoma were studied from the C-130 largely from the outside, while Project Rough Rider from Wright Field penetrated some of the storms. We also had ground guidance from NOAA’s severe storm group. My picture from the C-130 (a 9x9 camera) appeared a a double page spead in Life Magazine:

Life’s caption reads, “Its top an anvil of cloud 100 miles long, a great storm in the fullness of its wrath looms 50,000 feet above the patchwork fields and meandering streams of western Oklahoma. Photographed from an Air Force plane, the storm fed on the clouds moving in from the right, sucking them up its center and gaining violence from heat they released as they rose. It was 50 times more powerful than the bomb that struck Hiroshima; it battered two states with hail and lightning.”

“

1979~1983 I retired from AFCRL and joined THE United nations WORLD METEOROLOGICAL ORGANIZATION

I joined a new enterprise of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO part of the UN). I had a four-year, part time association with WMO as the field director of PEP, (Precipitation Enhancement Project). This was certainly a new experience for me; the WMO was being flooded with requests from various countries of the world for information on the reality of useful rainfall from weather modification projects. These were projects being proposed by a number of commercial enterprises. Countries that contributed scientists and equipment to PEP were Canada (radar measuring devices), France (radar, Satellite pictures, & an aircraft), Spain (site support, & radiosonde), USA (aircraft – Univ. of Wyoming), USSR (a large radar), Switzerland (disdrometer - raindrop spectrum), Bulgaria, and Yugoslavia. This project continued for several winters in the field in the Duero river valley in the region of Castile Spain and then in Geneva for the analysis phase.

A RETURN TO THE FOG via KENT ISLAND

After I retired from my full time job with AFCL and finished with my WMO/UN job and some consulting work with Weather Services Inc I finally was able to spend full time on my non-paying work on Grand Manan and Kent Island. Peter Summers and I decided it would be interesting to compare the acid and SO4 values obtained in fog water in 1938 and 1939 with some new measurements to be taken in 1983 & 1984

Myself (on pipe) holding several wind instruments on the warden's house on Kent Island. - - photograph by Jim Cunningham

By 1988 I had strong support for a number of years, equipment and chemical analysis, from Prof. Dick Jagels and Jobie Carlisle of the University of Maine (Orono) as the eastern most station in their string of stations along the Maine coast. They were tackling the effect of acid fog on red spruce. I was a coauthor of several published papers from this group. I continued my work on acid fog with the help of Roger Cox of the Canadian Forestry Service who was studying the effect of acid fog on birch trees. One season I contributed to a large project on North Atlantic pollution as part of the contribution of Stephen Beauchamp from Environment Canada in Bedford N.S. Much of the work on fog statistics and on fog chemistry was published in the Vancouver fog conference procceedings.

.

2001 A SLOW NEWS DAY

In August of 2001, a reporter and photographer came up to Kent Island to do a small article on Chuck Huntington and myself. About a week later we were quite surprised to see a long article in the Boston Sunday Globe, on page ONE, top of the fold, with a picture of the fog collector and myself on the front page.

A patient breed

For 64 years, scientist watches fog roll on By Beth Daley, Globe Staff,

8/5/2001 KENT ISLAND, New Brunswick - Franklin Roosevelt was president and World War II had not yet begun when Massachusetts high school student Bob Cunningham visited this remote island and picked the only thing he could see to study: Fog.

Sixty-four years later, when the mist rolls in on Kent Island in the Bay of Fundy - and it rolls in a lot - the retired cloud physicist is still there, capturing, cataloging and on occasion praying for even more of the mist that shrouds the island. Cunningham, 82, along with 81-year-old colleague Chuck Huntington, who has been studying birds on the island for a half-century - just may be the two longest-serving researchers of any single scientific study in North America.

Cunningham studies one facet of fog - acidity - sometimes with financial backing, sometimes not, but always for science's sake. He smiles when asked if he has found anything stunning about fog in his six decades of study (''not really''). Still, he and Huntington represent a type of scientist in increasingly short supply these days: those who measure the same subject - no matter how dry - over long periods of time. ''Let's face it, these studies are not as sexy as leaping onto the latest molecular biology bandwagon,'' said Nat Wheelwright, director of the Bowdoin College Scientific Station on Kent Island.

Not as convenient either. The college owns the 2-mile-long island, which is surrounded by treacherous rocks and tides that can fluctuate 20 feet in a day. Fog hovers on the island so often that a seaweed- like lichen hangs from tree branches. The only way to reach the island is to take a ferry from Blacks Harbour in New Brunswick to Grand Manan Island and then trust a small-boat captain to navigate the rocks to reach the research station 5 miles away.

''People get bored, they get tenured, they move on, and there is such a premium on quick and flashy research. But we need people to get this baseline data, these benchmarks,'' Wheelwright said. ''It takes unending curiosity, diligence and well, you've got to live a long time.'' It's not that scientists don't understand the value of long-term research. Just as in medicine, where a handful of decades-long studies have helped unlock secrets to heart disease and cancer, longtime scientific studies are invaluable to understanding the environment and changes in it. Ecologists and climatologists cite the enormous gaps in data as impediments to studying global climate change over the past 100 years. The National Science Foundation even has a 20-year-old program to encourage long-term research into specific topics, such as the movement of nutrients on land and in water in the Arctic tundra.

''But it takes a certain breed to sit on projects for a long time,'' said Henry Gholz, director for the Long Term Ecological Research program at the Science Foundation. The program funds projects for longer than the one to three years that are typical with both government and foundation grants.

Though there is no official record of long-serving researchers, scientists at institutions ranging from Massachusetts Institute of Technology to the National Academies of Sciences could not recall any scientist continuing a study for as long as Cunningham. Huntington, who studies virtually everything about small, slate-gray birds that burrow underground called storm-petrels, is running a close second, the scientists estimate.

But the two, who both sleep and research in shacks a few hundred feet from each other - and share an outhouse - seem oblivious to their stature. They remain solely devoted to data and, while funding is sporadic, they've continued their low-budget research virtually every year since they began.

''I guess I've never been imaginative enough to try something else,'' said Huntington before breaking into a brisk jog to retrieve binoculars left down a path. ''How does it feel to study storm-petrels this long? It's taken a long time to figure out how it feels.

'' Days on the island over the years tended to be solitary - long hours of research punctuated by the occasional dinner with visiting scientists and college interns, as well as Scrabble or maybe card games. Once in a while, Cunningham and Huntington would talk about their research, perhaps mention a notable find, but they share remarkably few science tales. Both men are taciturn Yankees who were too busy making the most of their short scientific season on the island.

As they've gotten older, the two are more often on the island at different times. Cunningham lives in Lincoln, Mass., during the winter, and usually comes out for a day to several at a time during the warm weather. He collects data and then returns to a summer house he shares with his wife on Grand Manan. However, he suffered a head injury in a fall last month and has only made it to the island twice since then. Huntington, of Harpswell, Maine, tends to stay for a few weeks at a time, rising at dawn to hunt petrels and then moving to a computer at the research station to log in data, sometimes late into the night.

But the two have a certain austere flair. Cunningham once had a boat called ''Fog Seeker'' and he still calls his shack ''Fog Heaven.'' The 6-by-6-foot shack is made in part with old windows from his house on Grand Manan, and a piece of foam on a seat serves as his bed. It's so tiny he has to sleep with his knees curled up, but he doesn't mind - he's an arm's length from data, and often, in the midst of fog.

Years ago, Cunningham and Huntington both would bring their children to the island - always careful to keep them on the tiny, barren island just long enough to keep them wanting to return. Now, the kids are long grown, but Cunningham's son Peter, a New York photographer, still posts pictures of Kent Island on his Web page.

Neither man set out to be science record-setters. After graduating from MIT, Cunningham spent the bulk of his career at an Air Force research laboratory at Hanscom Base in Bedford, working on weather forecasting to improve military flying operations.

Fog, however, has always been his great love. On Kent Island, Cunningham catches the mist pretty much the same way he caught it when he began in 1937: With a screen that captures droplets until they collect to form fog water. But now technology enters the picture, with a computerized testing system that samples the water for acidity and checks the air for wind speed and solar radiation every 10 seconds.

Measuring acidity in fog is an earlier and more sensitive indicator of atmospheric pollution than waiting for rain to fall. Over the years, Cunningham discovered that even a place as pristine as Kent Island can be hit with fog as acidic as vinegar. Next year, he plans to study mercury in the fog.

Professional associates:

Professor H.G. Houghton. My mentor in my graduate years at MIT and my degree supervisor.Dr Bernie Vonnegut. Head of the MIT Icing research project in the 1940’s. Later discovered the use of silver iodide as the most appropiate seeding agent for weather modification of supercooled clouds.

Alan Bemis, the head of the weather radar project in the meteorology dept.

Maj. (in those years) Jim Church my second “in command” in my cloud physics group at the AFCRL.

Rumen Bojkow, Bulgarian. Head of Atmospheric Physics in UN/WMO in Geneva.

Jack Warner Australian cloud physics. Head of proj.PEP from UN/WMO in Geneva.

Prof. Dick Jagels and Jobie Carlile. University of Maine, Orono, Forestry. Supported the Kent Island fog proj. for a number of years with chemical analysis and equipment.

Peter Summers, Canadian Atmospheric Environment Service, Project PEP and Kent Island fog experiments in ’83 &; 84,

Roger Cox, Canadian Forest Service, Fredericton N.B, Supported the KI fog experiments in recent years with chemical analysis and in year 2000 with a grant.

Scientific organizations:

Fellow of the American Meteorological Society.

Member of the Royal Meteorological Society

Member of the Canadian Meteorological Society.

Member of the American Geophysics Union.

Member of Sigma Xi

Member of the Mt Washington Observatory

References

Ingersoll, I. K. “Wings over the Sea” Goose Lane Editions. Fredericton, N. B. 1991

Daily, Beth. Boston Sunday Globe, August 5, 2001

Conover, J. H. The Blue Hill Observatory, The First 100 Years. 1885 – 1985, page 209. American Meteorological Society. (AMS). Boston MA. 1990.

Cunningham R.M. “Diary, 24June – 14 July 1937.” The first weeks on Kent Island

Cunningham R.M. “Diary, 13 August – 2 September 1947” Logbook for Claire

Cunningham, R. M. “Chloride content of fog water in relation to air trajectory”. Bull. AMS 22,17-20. 1941.

Dahl. F. W. “A cartoon” The Boston Herald, xxxxxx 19XX. Also in “Dahl’s Cartoons” Ralph T. Hale & Company 1943

Cunningham R. M. “Fog Studies In The Bay Of Fundy Over A Span Of 60 Years.” In R.S. Schemenauer (Environment, Canada) and H. Bridgman (Univ, of Newcastle, Australia) Eds. Proc. International Conference On Fog And Fog Collection. Page 153 1998 ***

Cunningham R.M. F. Sanders, “Into the Teeth of the Gale: The Remarkable Advance of a Cold Front at Grand Manan.” AMS Monthly Weather Review, Oct 1987

Cunningham R. M, D. Atlas “Growth of Hydrometers as Calculated from Aircraft and Radar Observations” In the Toronto Meteorological Conference 1953, AMS & Royal met Soc. 1953 p276-289

***These proceedings can be obtained from: Conference on Fog and Fog Collection

P.O.Box 81541 1057 Steeles Avenue West North York, Ontario, M2R 2x1 Canada

2022. Bob’s archived are currently being shipped to Cornell University for consideration. For more pictures of what is being shipped (and not shipped) see https://www.icloud.com/sharedalbum/#B0QJHciePJsawQb Contact son James Cunningham at jfc35@comcast.net or son Peter Cunningham at peterc@stilltv.com